Friday, August 31, 2012

Thursday, August 30, 2012

A Royal Wedding and Wedding Celebrations

The last sumptuous Russian state wedding took place over one hundred years ago – in 1894, when Nicholas II married the small-town German princess Alexandra. Shortly after their engagement, the reigning Tsar, Nicholas’s father Alexander III, unexpectedly died and thus, the bride-to-be came to Russia in the shadow of a hearse and the wedding took place one week after the funeral. A bad omen?

In fact, the story of Nicholas and Alexandra is another roulettian tale that includes hemophilia (their fifth child and only son/heir was stricken with this rare, life-threatening disease in which the blood does not clot), a questionable Siberian mystic (the infamous Grigory Rasputin who despite wild nights on the town was the only one able to ease the young boy’s suffering) and murder (Rasputin’s, in a ghastly palace slaughter that sought to remove his influence over Alexandra, thought to be destabilizing the monarchy and the country) and again murder (this time that of the royal family themselves).

Rasputin, who has been credited with unusual psychic abilities, penned a predictive warning to the royal couple late in 1916:

I feel that I shall leave life before January 1st.... if you hear the sound of the bell which

will tell you that Grigory has been killed, you must know this: if it was your

relations who have wrought my death then no one of your family, that is to say,

none of your children or relations will remain alive for more than two years.

They will be killed by the Russian people...I shall be killed. I am no longer

among the living.

I feel that I shall leave life before January 1st.... if you hear the sound of the bell which

will tell you that Grigory has been killed, you must know this: if it was your

relations who have wrought my death then no one of your family, that is to say,

none of your children or relations will remain alive for more than two years.

They will be killed by the Russian people...I shall be killed. I am no longer

among the living.

Twenty-three days later his bullet-ridden, poisoned corpse turned up in an icy tributary of the Neva river. And forebodingly, among Rasputin's murderers were relatives of the Tsar.

Within three months of Rasputin's horrific demise revolution swept across the land and blood flowed in rivers. Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias, Grand Duke of Finland, King of Poland, etc. etc., was now a humble prisoner stripped of all

rank. Along with Alexandra and their five photogenic children he was transported to Siberia, where the whole family was ruthlessly shot by the Bolsheviks in July 1918 -- twenty months after Rasputin’s murder, much as the mysterious Siberian had predicted. This effectively ended the Romanov imperial dynasty which had enjoyed autocratic might for over 300 years. Yet the red jacket in which Nicholas was married can still be seen today in the Alexander Palace. It is inscribed with the words "To be preserved forever.“

Within three months of Rasputin's horrific demise revolution swept across the land and blood flowed in rivers. Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias, Grand Duke of Finland, King of Poland, etc. etc., was now a humble prisoner stripped of all

rank. Along with Alexandra and their five photogenic children he was transported to Siberia, where the whole family was ruthlessly shot by the Bolsheviks in July 1918 -- twenty months after Rasputin’s murder, much as the mysterious Siberian had predicted. This effectively ended the Romanov imperial dynasty which had enjoyed autocratic might for over 300 years. Yet the red jacket in which Nicholas was married can still be seen today in the Alexander Palace. It is inscribed with the words "To be preserved forever.“

Meanwhile, weddings in Russia are usually pretty lavish affairs and summer is wedding season. Across Petersburg on any given day of the week you are apt to see luxurious white stretch limos gliding down main avenues and brides in ebullient dresses posing for photos at picturesque spots about town. Church weddings are generally avoided. As Golden Guy Pavel explains, "No one wants a church wedding. If you get married in the Orthodox Church, it’s almost impossible to get a divorce!“ The answer is the "wedding palace“ which works pretty much like an upscale justice of the peace.

Well, Nicholas and Alexandra have been accused of many things, including the demise of the Romanov dynasty, but no one has ever denied their enduring love which began at their first meeting (he was 17 and she was just 12) and continued until the day they were simultaneously shot. With the divorce rate in Russia today at about 50%, one can only hope that these smiling brides will end up on the happy side of statistics.

In fact, the story of Nicholas and Alexandra is another roulettian tale that includes hemophilia (their fifth child and only son/heir was stricken with this rare, life-threatening disease in which the blood does not clot), a questionable Siberian mystic (the infamous Grigory Rasputin who despite wild nights on the town was the only one able to ease the young boy’s suffering) and murder (Rasputin’s, in a ghastly palace slaughter that sought to remove his influence over Alexandra, thought to be destabilizing the monarchy and the country) and again murder (this time that of the royal family themselves).

I feel that I shall leave life before January 1st.... if you hear the sound of the bell which

will tell you that Grigory has been killed, you must know this: if it was your

relations who have wrought my death then no one of your family, that is to say,

none of your children or relations will remain alive for more than two years.

They will be killed by the Russian people...I shall be killed. I am no longer

among the living.

I feel that I shall leave life before January 1st.... if you hear the sound of the bell which

will tell you that Grigory has been killed, you must know this: if it was your

relations who have wrought my death then no one of your family, that is to say,

none of your children or relations will remain alive for more than two years.

They will be killed by the Russian people...I shall be killed. I am no longer

among the living.Twenty-three days later his bullet-ridden, poisoned corpse turned up in an icy tributary of the Neva river. And forebodingly, among Rasputin's murderers were relatives of the Tsar.

Within three months of Rasputin's horrific demise revolution swept across the land and blood flowed in rivers. Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias, Grand Duke of Finland, King of Poland, etc. etc., was now a humble prisoner stripped of all

rank. Along with Alexandra and their five photogenic children he was transported to Siberia, where the whole family was ruthlessly shot by the Bolsheviks in July 1918 -- twenty months after Rasputin’s murder, much as the mysterious Siberian had predicted. This effectively ended the Romanov imperial dynasty which had enjoyed autocratic might for over 300 years. Yet the red jacket in which Nicholas was married can still be seen today in the Alexander Palace. It is inscribed with the words "To be preserved forever.“

Within three months of Rasputin's horrific demise revolution swept across the land and blood flowed in rivers. Nicholas II, Emperor and Autocrat of all the Russias, Grand Duke of Finland, King of Poland, etc. etc., was now a humble prisoner stripped of all

rank. Along with Alexandra and their five photogenic children he was transported to Siberia, where the whole family was ruthlessly shot by the Bolsheviks in July 1918 -- twenty months after Rasputin’s murder, much as the mysterious Siberian had predicted. This effectively ended the Romanov imperial dynasty which had enjoyed autocratic might for over 300 years. Yet the red jacket in which Nicholas was married can still be seen today in the Alexander Palace. It is inscribed with the words "To be preserved forever.“ Meanwhile, weddings in Russia are usually pretty lavish affairs and summer is wedding season. Across Petersburg on any given day of the week you are apt to see luxurious white stretch limos gliding down main avenues and brides in ebullient dresses posing for photos at picturesque spots about town. Church weddings are generally avoided. As Golden Guy Pavel explains, "No one wants a church wedding. If you get married in the Orthodox Church, it’s almost impossible to get a divorce!“ The answer is the "wedding palace“ which works pretty much like an upscale justice of the peace.

Petersburg's most desirable wedding palace is on the same street as the U.S. Consulate

The ceremony is short, under fifteen minutes, in which a charming (cloying) official reads a charming (cloying) statement wishing all the best to the truly charming couple

A stretch limo for the bridal party

Two golden rings often decorate the limos

A pleasant chat on the carefully groomed grass

A spritely romp along the edge of the Neva River

Splashing in the waves

Weddings don't have to break the bank as this couple demonstrates. Why not enjoy a packaged ice cream cone instead of a fussy, elaborate cake? Nor, thankfully, must weddings prevent you from attending to important business on your handy cell phone.

Gee, shucks!

Is there anything left to say?

Well, Nicholas and Alexandra have been accused of many things, including the demise of the Romanov dynasty, but no one has ever denied their enduring love which began at their first meeting (he was 17 and she was just 12) and continued until the day they were simultaneously shot. With the divorce rate in Russia today at about 50%, one can only hope that these smiling brides will end up on the happy side of statistics.

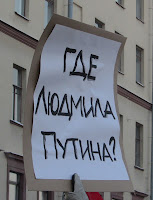

One might also ask, as does the sign on the left, where is Ludmila Putin? Putin’s

wife has virtually disappeared from public view, although she made a brief

appearance at his inauguration back in May. Rumors abound, but two receive the most attention. Either she is with her two daughters

who are studying abroad (although no one seems to know where) or, following in

the good old Russian footsteps of such Tsars as Peter the Great, Putin has

stashed the burdensome wife away in a monastery.

Monday, August 27, 2012

Roulettian Intermezzo -- Photo of the Week

A young girl offers bread to a host of eager pigeons in the courtyard of the Anna Akmatova museum.

And who was Anna Akmatova? One of Russia's most important 20th century poets, who knew hardship and tragedy and how to write about them. Her husband was shot by the Bolsheviks in the early 1920s (the reprieve issued by Lenin arrived too late to stop the bullet) and her son endured several lengthy imprisonments under Stalin's brutal repressions, during which it was unclear whether he would survive the arduous ordeals. Akmatova described the unendurable horror of this situation in her wrenching poem Requiem ("husband dead, son in jail, pray for me"), which because of its sensitive topic was not allowed to be published in the Soviet Union until 1987. Surely Russia has become a better place if her apartment is now a museum-shrine and pigeons feast in her courtyard.

Sunday, August 26, 2012

The Gambler and Anatoly Alone

We mentioned some time ago that the magnificent Russian

author Fyodor Dostoevsky was addicted to roulette and at one particularly low

point even pawned his wife’s wedding ring. Coincidentally, his dreadful gambling habit actually led

to meeting this wife in the first place.

We mentioned some time ago that the magnificent Russian

author Fyodor Dostoevsky was addicted to roulette and at one particularly low

point even pawned his wife’s wedding ring. Coincidentally, his dreadful gambling habit actually led

to meeting this wife in the first place.

In late September 1866 Dostoevsky was (again) in desperate need of funds in order to pay off gambling debts. So he entered into a chancy contract with a publisher, promising that he would complete a new novel by 1 November. If this strict deadline was not met, the publisher would acquire the right to publish Dostoevsky’s works for the next nine years without any compensation to the author.

With little more than a month at his disposal, Dostoevsky had not yet written a single line. The situation was dire and at the suggestion of a friend, he hired a stenographer to assist in this gargantuan task – Anna Snitkina. She began work on 4 October and amazingly, the novel was completed 26 days later, on 30 October. It was titled The Gambler and was partially based on Dostoevsky’s rather vast experience in the casinos of Europe. So impressed was Dostoevsky with Anna that in November 1866 he proposed and in February of the next year the two were married. For the rest of his life, Anna remained an invaluable help to the brilliant author: in addition to her massive stenographical work on all of his future novels, she also managed finances and negotiations with publishers, and soon eliminated Dostoevsky’s debts. In 1871, he gave up gambling for good.

With little more than a month at his disposal, Dostoevsky had not yet written a single line. The situation was dire and at the suggestion of a friend, he hired a stenographer to assist in this gargantuan task – Anna Snitkina. She began work on 4 October and amazingly, the novel was completed 26 days later, on 30 October. It was titled The Gambler and was partially based on Dostoevsky’s rather vast experience in the casinos of Europe. So impressed was Dostoevsky with Anna that in November 1866 he proposed and in February of the next year the two were married. For the rest of his life, Anna remained an invaluable help to the brilliant author: in addition to her massive stenographical work on all of his future novels, she also managed finances and negotiations with publishers, and soon eliminated Dostoevsky’s debts. In 1871, he gave up gambling for good.

The Dostoevskys' summer home -- the only piece of real estate they every owned -- is now a beautifully restored museum.

Tbis is the humble desk where Dostoevsky penned a large portion of his astounding Brothers Karamazov, arguably the best novel ever written. Much of the story was set in a fictitious version of Staraya Russa.

Ach, the glove that touched the hand that wrote Brothers Karamazov!

Dostoevksy's summer home is located on the banks of a river that seems a fitting subject for a painting by Monet.

Today Staraya Russa, one of the oldest towns in the nation, remains a charming, bucolic spot, perched on the banks of the Polist River.

The Church of the Resurrection reflects in the river's still waters under the cool northern sun.

People sunbathe and swim....

...and watch the water drift by.

Gee, this woman looks like she could be from New Jersey!

Two grandmas sit congenially (?) in the summer sun.

Well, there is still some time before it's

necessary to catch the bus out of town, and a little nourishment sounds like a

good idea, so I head into an, ahem, atmospheric cafe on what appears to be a

main lane in this outback town. A foreboding of the clientele is provided via the

alcoholic artwork in the window.

Well, there is still some time before it's

necessary to catch the bus out of town, and a little nourishment sounds like a

good idea, so I head into an, ahem, atmospheric cafe on what appears to be a

main lane in this outback town. A foreboding of the clientele is provided via the

alcoholic artwork in the window.

Not long after I sit down with a paltry slice of

white bread topped by paper-thin meat and cucumber, Anatoly separates himself from the

group of imbibers at the next table and joins me. I suggest juice or

perhaps even beer, but he insists on a round of vodka that comes served in glasses fit for water. After one gulp down the

hatch he starts talking.

"Why," he asks, "did we ever destroy

communism? Back then there was work, everyone had jobs, everyone had

medical care. Now all the factories here have been closed down. Me, I'm driving

a mini bus around town, 6o dollars a shift, sometimes I do two shifts.

Everything is bad and it's only going to get worse."

"Why," he asks, "did we ever destroy

communism? Back then there was work, everyone had jobs, everyone had

medical care. Now all the factories here have been closed down. Me, I'm driving

a mini bus around town, 6o dollars a shift, sometimes I do two shifts.

Everything is bad and it's only going to get worse."

At one point in a past that seems separated from

the present by an uncountable amount of time, Anatoly apparently had two or

maybe even three apartments. Unclearly, he somehow managed to be divested of

them and would be homeless now were it not for his friend Sergei, an

"Afghanets" -- Sergei served in the Soviet Army in Afganistan back in

the 80s and became disabled during that long, brutal war. But his pension isn't

enough to live on, and so Anatoly is saving the day by paying for food and

utilities -- and it seems alcohol. He orders another round.

"I had a girlfriend," he continues

morosely, "we were together a long time, but she died a month ago. She was

49. I never saw her sober. And then she kicked the bucket on me. Now I'm all

alone -- well, I guess, except for Sergei...."

"I had a girlfriend," he continues

morosely, "we were together a long time, but she died a month ago. She was

49. I never saw her sober. And then she kicked the bucket on me. Now I'm all

alone -- well, I guess, except for Sergei...."

He wants me to meet Sergei and says he'll fix me a

bowl of the tasty Russian cold summer soup, but -- time is up, and given

Anatoly's state of sobriety, I doubt that the promised soup would ever

truly be served. He accompanies me to the bus stop, picking up a bottle of

vodka along the way for him and Sergei to share. As the bus pulls out, Anatoly

waves good-bye with one hand and clutches the bottle of vodka with the

other. Characters worthy of Dostoevsky's novels are still roaming the lanes and ale houses of Russia.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)